Indian Trails of Niagara - Indigenous Byways to Regional Highways

Overview

• For thousands of years Indigenous people have hunted in the Niagara area and have fished the shores of Lake Ontario or the Niagara River and its tributaries.

• Pathways were developed following animal trails in pursuit of game or to link the villages that developed in the Peninsula.

• Trade was an important aspect of life long before Europeans arrived on the scene with hunters exchanging meat and pelts and farmers exchanging corn, beans, squash, and tobacco, while fishers exchanged their catch with other traders who brought wampum from the East Coast, pipestone from present day Oklahoma, copper from north of Lake Superior, and a variety of goods from all over eastern North America.

• Traders used canoes when navigable waters were feasible and followed the trails when they were not. Trails tended to follow the paths of least resistance, leading around swamps and leading to portage routes around river rapids and fording places over creeks, and taking the routes of the easiest slopes up and down obstacles like the Niagara Escarpment.

• With the arrival of the Europeans and their settlement in Niagara following the American Revolution, the new settlers relied on the same technology, foot power or canoes for travel to other settlements, following the ancient trails that had been used for millennia.

• For the British military, roads were needed to move their supplies by horse or ox drawn wagon and to move their artillery from post to post.

• Farmers needed roads to enable them to haul their produce to market in wagons and carts. While totally new roads were cut through the bush to meet the requirements of settlement, other roads were built by widening existing trails.

• In several places the new roads crossed swampy land over which heavily laden wagons would bog down. Corduroy roads, logs laid side by side, overcame the mud of such places while making the users suffer a very bumpy ride over the corrugated surface.

• Bridges were built where required.

• Today, major roads linking Hamilton to Niagara, the Niagara Parkway, Portage Street in Niagara Falls, Highways 81 and 87, Four Mile Creek Road, and many others largely follow the paths first travelled not long after the glaciers retreated, and glacial Lake Iroquois shrank back to form Lake Ontario.

Details

Dave Brown, Dept. of Geography and Tourism Studies, Brock University

• Trails and pathways have existed in Niagara since the arrival of humans. They were first established by First Nations peoples for navigating the Niagara landscape in their quest for wildlife resources while living as advanced hunter-gatherers, from at least the 1300s. Animal trails (e.g., deer runways) were utilized, hunting trails were established to pursue deer, raccoon, wolves, wild cats, squirrels, beavers and turkeys, and fishing trails were established along watercourses for line fishing, trapping, and seining.

• The Onguiaahra and Chonnonton tribes were the first to settle the region. Their preferred mode of travel was on the waterways by canoe, but they also had extensive networks of foot trails throughout the territory, including along waterways for portage routes.

• The first European documentation of Indigenous human residents occurred by the French in the early 1600s. Champlain and French Jesuit priests described Iroquoian-speaking North American indigenous people collectively as les Neutres or the Neutral Nation (because at the time, they were not at war with the adjacent Iroquois and Huron peoples, and traded flint from their territory with both of the warring sides).

• The Neutrals had several semi-permanent settlements in the Niagara Peninsula (estimated at 40 villages with about 12,000 people in the early 1600s), consisting of longhouses within timber enclosures and adjacent agricultural land. These were connected by trails and pathways to the surrounding landscape.

• After 20-40 years of habitation, game and timber resources and soil fertility near the semi-permanent settlements would become depleted, necessitating the establishment of new settlements in virgin areas. Small-scale local trails in resource-depleted areas would eventually grow in.

• Despite this semi-sedentary lifestyle, the Neutrals had a well-established network of trails and pathways in Niagara that they used for hunting, foraging, and trade. These paths followed natural landscape features like the Escarpment, the lakeshores, and the streams and rivers, forming a well-used regional trail complex. Smaller local trails were also established between settlements, foraging areas, fishing and hunting sites, and agricultural plantations.

• By 1653, the Neutrals were essentially vanquished by a combination of introduced European diseases and invasion by the Iroquois. After the second half of the 17th century, permanent First Nations settlements in Niagara had all but disappeared, so the network of fine-scale local trails grew in. However, the major east-west arterial trails persisted, facilitating passage across the peninsula for adjacent Haudenosaunee peoples for the purposes of hunting, trade, and warfare.

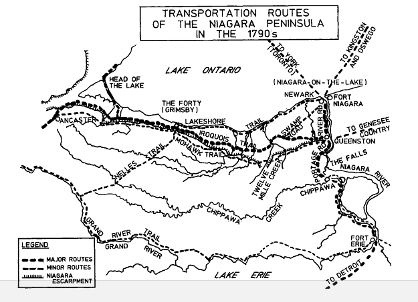

• The first comprehensive mapping of Native trails was done by Burghardt in 1777 (see map).

• By this time, major trails were primarily east-west in orientation, and would later form the basis of the early transportation networks of the early European settlers. Many of these trails still form the basis of our modern road infrastructure today.

• Regional trails in Niagara converged most notably at the approximate location of Shipman’s Corners in St. Catharines and helped to define the location of that European settlement. The three most important First Nations trails were the Iroquois Trail, the Mohawk Trail, and the Lakeshore Trail.

• The Iroquois Trail followed the base of the Niagara Escarpment from Queenston to Ancaster. It avoided difficult terrain and stayed south of the mouths of the rivers that widened closer to Lake Ontario. It effectively became the historic ‘express route’ across Niagara. Its trajectory helped define the location of several European settlements in Niagara and was responsible for the curving sweep of St. Paul Street in St. Catharines. Queenston, St. Davids, St. Catharines, Jordan, Beamsville, Grimsby, Stony Creek, Hamilton, and Ancaster arose along its length. The route was adopted by old Ontario Highway 8, now Regional Road 81, and it still fulfills an important transportation role to this day.

• The Mohawk Trail was the ‘high road’ along the top of the escarpment, paralleling the Iroquois Trail from St. David’s to Ancaster. The two trails were seldom more than 3-4 km apart. It was used as an elevated alternative route during wet weather when lowlands were flooded, and when added elevation provided vistas that were useful for hunting or warfare. Its modern counterpart includes sections of St. David’s Road, Decew Road, and Pelham Road, as well as sections of Ridge Road, Mohawk Road, and other roadways along the brow of the Escarpment all the way to Ancaster. The section along present-day Decew Road was the location of both the famous Decew House, the 1813 destination of Laura Secord, and of Decew Town, a settlement of homes, mills, and businesses that made use of the water in Beaverdams Creek and Decew Falls before the Welland Canal diversions reduced the flow. The thriving settlement of St. Johns was also found just to the south, established along a series of native pathways through the Short Hills region. At the eastern end, the Mohawk Trail continues on the opposite side of the Niagara River in upstate New York towards Genesee County and beyond.

• The Lakeshore Trail, which followed the shore of Lake Ontario from Queenston to Grimsby, was less important and less travelled than the Iroquois and Mohawk Trails, since it was broken up repeatedly by the mouths of the creeks that drained the Escarpment into Lake Ontario. Its modern trajectory is approximated by the Niagara Parkway and Lakeshore Road / Regional Road 87 in Niagara-on-the-Lake and St. Catharines. It would have paralleled the lakeshore north of the QEW, but the original route has been fragmented by agricultural and residential development along the lakeshore.

• Other trails along watersheds and near sacred lands have also persisted. For example, a trail following modern-day St. David’s Road / St. Paul Avenue (Regional Road 100) followed Four Mile Creek towards Niagara Falls, passing by the large Neutral Indian ossuary established in the sandy soils west of Eagle Valley Golf Club.